A handful of online encoders are constructed and compared in this post. The raw notebook can be found here.

Motivation

Recently, I had to encode a large number of strings with integers. The strings were not known in advance for they were coming from a generator. The generator itself took a list of strings and sanitised them e.g. removed trailing whitespaces.

I try to use generators as much as I can in order to save memory (we are concerned with strings in the order of millions).

Unfortunately, the encoder utility LabelEncoder of sklearn has to know all strings in advance. It therefore cannot be used as an online encoder.

Random string sequences

We need a source of random string sequences to test the future encoders. Below, we write a generator object (or factory), random_string_sequence_generator_factory that yields random string generators. This function can be viewed as an infinite resource of sequence generators. It is really similar to our Markov chain generator MarkovSequenceGenerator.

import random

import string

def random_string_sequence_generator_factory(character_pool,

string_length = 1,

sequence_length = 10):

"""

Creates a generator or fixed length random string sequences.

Please note, this is a generator object that yields a sequence generator.

Parameters:

character_pool (str) : alphabet

string_length (int) : length of the random strings

sequence_length (int) length of the sequence containing random strings

Yields:

new_generator (generator) : generator of string sequences.

"""

# creates a sequence of random strings

def sequence_generator(character_pool_, string_length_, sequence_length_):

"""

Creates a random sequence generator.

We deefine local arguments, to avoid infiltration from outer namespaces.

In jupyter, it can be a very likely scenario.

Parameters:

character_pool_ (str) : alphabet

string_length_ (int) : lenght of the string

sequence_length_ (int) : length of the sequnce

Returns:

sequence (generator) : generator of random string sequence

"""

sequence = (''.join(random.choices(character_pool_, k = string_length_))

for idx in range(sequence_length_))

return sequence

# create an infinite resource of generators

while True:

new_generator = sequence_generator(character_pool, string_length, sequence_length)

yield new_generator

A generator is created which produces generators of eleven element long sequences of two character random strings.

random_sequence_generator = \

random_string_sequence_generator_factory('abcdefghijklmnopqrstyuvwxyz',

string_length = 2,

sequence_length = 11)

Let us consume the first element:

seq_gen1 = next(random_sequence_generator)

print(seq_gen1)

<generator object random_string_sequence_generator_factory.<locals>.sequence_generator.<locals>.<genexpr> at 0x0000027D66FC1BA0>

As we expected a generator object is returned. Now we spend the generator:

print(", ".join(seq_gen1))

ua, fq, wf, uz, cj, yd, ao, qn, xp, ai, vx

Consume more sequences:

for idx in range(7):

seq_gen = next(random_sequence_generator)

print("Seq no.: {0}. Sequence: {1}".format(idx, list(seq_gen)))

Seq no.: 0. Sequence: ['ir', 'va', 'nk', 'wk', 'pq', 'wy', 'xq', 'yq', 'rp', 'fc', 'yz']

Seq no.: 1. Sequence: ['mu', 'rr', 'uf', 'nk', 'lz', 'yc', 'jr', 'jk', 'va', 'iy', 'ae']

Seq no.: 2. Sequence: ['xx', 'vw', 'bb', 'ia', 'ms', 'iz', 'yw', 'yu', 'cl', 'qh', 'ph']

Seq no.: 3. Sequence: ['we', 'bc', 'wp', 'dg', 'up', 'fw', 'nu', 'pi', 'bk', 'rj', 'wb']

Seq no.: 4. Sequence: ['ey', 'im', 'vc', 'yg', 'bi', 'lo', 'cw', 'jl', 'yn', 'nw', 'ys']

Seq no.: 5. Sequence: ['zh', 'rj', 'jd', 'nn', 'iz', 'fj', 'kv', 'zm', 'sw', 'vg', 'fp']

Seq no.: 6. Sequence: ['mh', 'qa', 'qy', 'yt', 'ph', 've', 'fg', 'oy', 'ib', 'tb', 'mw']

Encoders

An encoder takes and object and assigns a unique value to it. It also needs to be consistent. A certain object always associated with the same value.

- initialise lookup table

- obtain object

- look for object in lookup table

- if present

- return associated value

- if not

- create new value

- save (object, value) pair in lookup table

- return value

It is clear that an encoder has an associated memory and functions that interact with this memory.

The functions operating on the memory:

- lookup function

- saves pair

We also need a function that can generate unique values. This function has to be aware of the used values and has to implement a rule that generates a new value based on the used ones. The used values can either be exrtacted from the memory (lookup table) or stored in a different memory.

The encoder thus can be defined as a tuple of the following components

- lookup table

- lookup function

- function to generate new value

- function to push (object, value) pair to lookup table

- and at last, function to return value

List encoder

The first implementation, _encoder_1 based on the tuple model. We use a list to store the components of the encoder, for tuple are immutable in python.

from itertools import count

_encoder_1_ = [

{},

count(),

lambda x: encoder[0].update({x : next(encoder[1])}),

lambda x: (encoder[2](x), encoder[0][x])[1]

if x not in encoder[0] else encoder[0][x]

]

-

{}: the first element of the list is the lookup table, a simple dictionary. -

count(): the second element, has dual functions.- It serves as a memory to store the used values

- It can provide new values whenever its

nextmethod is called

-

encoder[0].update({x : next(encoder[1])}): the third element does the followingnext(encoder[1]): creates a new value- stores the used values (

countcannot go backwards) encoder[0].update({... : ...}): puhes the (object, value) to the lookup table

-

The fourth element comprises of a manifold steps:

- it decides whether the object is in the lookup table

else: if so,encoder[0][x]: returns the corresponding value.... else encoder[0][x]

if x not in encoder[0]if not,encoder[2](x): creates a new (object, value) pair- saves the new pair

encoder[0][x]: retrieves the value from the lookup memory(..., ...)[1]: pushes the value to the user

We would like to make this encoder to be reusable hence it is wrapped in a factory function, create_encoder_1

def create_encoder_1():

_encoder = [

{},

count(),

lambda x: _encoder[0].update({x : next(_encoder[1])}),

lambda x: (_encoder[2](x), _encoder[0][x])[1]

if x not in _encoder[0] else _encoder[0][x]

]

encoder = lambda x: _encoder[3](x)

return encoder

For testing purposes one character long strings are used so that we can see whether the encoding is consistent.

random_sequence_generator_1_10 = \

random_string_sequence_generator_factory('abcdef',

string_length = 1,

sequence_length = 10)

Let us test our encoder:

encoder_1 = create_encoder_1()

print([(string, encoder_1(string))

for string in next(random_sequence_generator_1_10)])

[('b', 0), ('e', 1), ('b', 0), ('c', 2), ('b', 0), ('b', 0), ('b', 0), ('b', 0), ('b', 0), ('e', 1)]

As we can see the encoding is both unique and consistent. Decoding requires access to the lookup table, which is now hidden because of the convenience $\lambda$-wrapper.

Function decorator

From a practical point of view, an encoder is a function with an associated memory. If we can associate a storage with a lookup function, we can build an encoder. A convenient tool is a decorator. The associate_lookup decorator locks the lookup and used value memories to a function. The function itself encoder_2 is a dummy. Its only role is to provide acces to the memory. A factory is also created for this encoder.

def associate_lookup(func):

store = [-1, {}] # value, lookup

def lookup_(x):

if not x in store[1]:

store[0] += 1 # generate unique values

store[1].update({x : store[0]}) # push new relation to lookup

return store[1][x] # push value to user

return lookup_

def create_encoder_2():

"""

Factory for encoder_2.

"""

@associate_lookup

def encoder(x):

pass

return encoder

We test it on a random one letter sequence:

encoder_2 = create_encoder_2()

print([(string, encoder_2(string))

for string in next(random_sequence_generator_1_10)])

[('f', 0), ('a', 1), ('d', 2), ('a', 1), ('f', 0), ('f', 0), ('e', 3), ('f', 0), ('b', 4), ('c', 5)]

Again, it is unique and consistent. This implementation has a major drawback: the lookup table cannot be accessed, thus the encoded values cannot be decoded. A possible, and rather ugly, solution is to add a decoding table to store. The new function would also require a second argument that specifies which lookup table should be used. This function will not be implemented, for it would only deliver a very modest degree of joy and aesthetic satisfaction.

Function attributes and decorator

Functions can have user defined attributes. The associate_explicit_lookup decorator explicitly bounds the idx and lookup fields to a function. Both of them are visible to the user.

def associate_explicit_lookup(func):

func.lookup = {}

func.idx = -1

return func

def create_encoder_3():

@associate_explicit_lookup

def encoder(x):

if not x in encoder.lookup:

encoder.idx += 1

encoder.lookup.update({x : encoder.idx})

return encoder.lookup[x]

return encoder

A test confirms below that the encoder works correctly (well, as far as being unique and consistent goes on a small sample).

encoder_3 = create_encoder_3()

print([(string, encoder_3(string))

for string in next(random_sequence_generator_1_10)])

[('f', 0), ('b', 1), ('e', 2), ('c', 3), ('d', 4), ('a', 5), ('e', 2), ('a', 5), ('b', 1), ('c', 3)]

The memory of the function is readily accessible

print("Lookup table: {0}".format(encoder_3.lookup))

print("Number of keys: {0}".format(encoder_3.idx))

Lookup table: {'f': 0, 'b': 1, 'e': 2, 'c': 3, 'd': 4, 'a': 5}

Number of keys: 5

Encoder class

A classy solution is to bundle the various components of the encoder in the form of named fields. This, third approach is that of the object oriented programming. (We have been creating objects in the previous two implementations too, but in an implicit way.)

Writing classes has many additional advantages, e.g. maintainable code, adding functionalities, easy manipulation of the underlying fields. The Encoder class below implements the encode, decode and reset methods.

class Encoder:

"""

Lightweight encoder -- decoder class.

Methods:

encode(x) : returns the code of x

decode(x) : returns the value that is encoded by x

reset() : clears memory

"""

def __init__(self):

self._idx = -1

self._encode_map = {}

self._decode_map = {}

def encode(self, x):

"""

Encodes a hashable object with an integer.

Parameters:

x (object) : value to encode

Returns:

(int) code of x

"""

if not x in self._encode_map:

self._idx += 1

self._encode_map.update({x : self._idx})

self._decode_map.update({self._idx : x})

return self._encode_map[x]

def decode(self, x):

"""

Dencodes a hashable object with an integer.

Parameters:

x (int) : value to encode

Returns:

the value that is encoded by x

"""

return self._decode_map[x]

def reset(self):

"""

Clears lookup tables.

"""

self._idx = -1

self._encode_map = {}

self._decode_map = {}

encoder_4 = Encoder()

# encode

print("Encode:")

print([(string, encoder_4.encode(string))

for string in next(random_sequence_generator_1_10)])

# encode and decode

print("\nEncode -- decode:")

print([(string, encoder_4.decode(encoder_4.encode(string)))

for string in next(random_sequence_generator_1_10)])

Encode:

[('e', 0), ('a', 1), ('a', 1), ('d', 2), ('a', 1), ('a', 1), ('a', 1), ('f', 3), ('d', 2), ('f', 3)]

Encode -- decode:

[('f', 'f'), ('a', 'a'), ('f', 'f'), ('e', 'e'), ('a', 'a'), ('f', 'f'), ('c', 'c'), ('e', 'e'), ('f', 'f'), ('c', 'c')]

Comparison

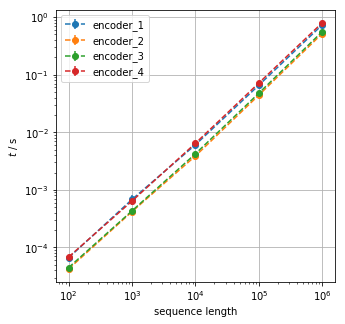

The performance of the four encoders are compared below. We could have used the SimTimer class, which also had given opportunities to write more decorators and generators. However, I doubt anyone would debate how refreshing scribbling a few for loops can be.

The string length is set to eight. The sequence lengths are 100, 1000, 10000, 100000, 1000000. Each size contains five different sequences.

We do not want to contaminate our mesurements with the time that is needed to generate the random sequences, thus they are saved in memory in the 2D list called test_sequences in advance.

test_sequences = []

for sequence_length in (100, 1000, 10000, 100000, 1000000):

rsg = random_string_sequence_generator_factory('abcdefghijklmnopqrtstyuvwxyz',

string_length = 8,

sequence_length = sequence_length)

test_sequences.extend([list(next(rsg)) for idx in range(10)])

We then collate the encoders with their names in the encoder_factories tuple. The second element of the tuple creates a callable encoder.

encoder_factories = (

('encoder_1', create_encoder_1),

('encoder_2', create_encoder_2),

('encoder_3', create_encoder_3),

('encoder_4', lambda: Encoder().encode) # mild lambda abuse

)

The perf_counter function of the time module will mesaure the execution time. The variables are collected in the results list of tuples.

import time

# store execution times

results = []

# loop over arrays

for seq in test_sequences:

# loop over encoders

for name, factory in encoder_factories:

# create decoder

encoder = factory()

# measure execution time

tstart = time.perf_counter()

_ = [encoder(x) for x in seq]

tend = time.perf_counter()

tdelta = tend - tstart

results.append((name, len(seq), tdelta))

The results are easily processed by a few pandas operations. Alternatively, one could use seaborn.

import pandas as pd

results_df = pd.DataFrame(results, columns = ['type', 'size', 'time'])

stats_df = results_df.groupby(['type', 'size']).describe()['time'][['mean', 'std']]

stat_groups_df = stats_df.groupby(level = 0)

The mean execution times are then plotted against the sequence size along with the standard deviation. (The deviations are barely visible, but present.)

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(5, 5)

ax.set_xscale('log'); ax.set_yscale('log')

ax.set_xlabel('sequence length'); ax.set_ylabel(r'$t$ / s')

ax.grid(True)

for name, data in stat_groups_df:

x = data.index.get_level_values(1)

ax.errorbar(x, data['mean'], yerr = data['std'],

fmt = '--o', label = name)

ax.legend()

plt.show()

There is not a tremendous difference between the various encoders. The class and tuple implementations are approximately 20% slower than the ones using decorators. The choice of method therefore the class implementation.